Co-enquiring the multisensory ecologies of school buildings with a group of Year 12s through participative sensory-digital methods

Laura Trafí-Prats, Project PI and Senior Lecturer at the School of Health and Education, Manchester Met University

A central aim of the project Mapping Spatial Practices and Social Distance in Smart Schools is to develop methods of mapping the sensory-affective dimension of school atmospheres by using participatory ethnography and sensory-digital methods (Pink 2009; Pink et. al. 2016). Such participation has involved the collaboration of members of the team, Trafí-Prats, Duggan and McCauley with groups of secondary school students in researching their everyday experience of the school environment. Engaging young people in processes of sensory ethnographic research helps to bring their attention to the digital and sensory elements shaping the experience of architecture of the school building (Pallasmaa, 2012). Our project, sought to extend young people’s awareness on how the design of school buildings could shape multisensory experiences that enhance life, well-being, and learning (Spence 2020). Participatory sensory-digital ethnography not only captures the experiences of participants but develops knowledge and experience with them to create change together (Pink, 2014). Thus, we used artistic and creative methods to deploy opportunities for young people to attune to the multisensory aspects of school environment and immerse in a sensorially rich spatial awareness to eventually imagine and devise potential environmental enhancements affecting the quality of life and learning in the school building (see later blog entry centered on Ling Tan workshops).

Following this framework of ideas, during the months of November 2021 to January 2022, Trafí-Prats, Duggan, and McCauley delivered six workshops with a group of fourteen Year 12s in one of our participating schools in Liverpool. The goals of the workshops were: a) to develop a robust relationship between the research team and the school; b) to develop participant awareness of the built environment and the sensory ecology of the building; c) to empower the participants in the use of cameras, different types of sensors, and spatial scanners so in later phases of the study students could participate as co-ethnographers. After a process of consultation with the school, its headteacher, curriculum coordinator and art department lead, 14 students from an A-level art class were selected to participate in the study.

One of the challenges that we faced when collaborating with this group of students was gaining their trust and active participation. In our first session, we decided to work with the entire group, but soon we recognised the difficulty of engaging in conversation and involving them in participative activity. Two teachers attending this first session informed us that they were not surprised of such response and that getting students to participate in a class discussion or to produce creative work often took time and further supervision. We also considered that the topic of investigating their own relations and experience with the building and its design was qualitatively different to the methods and techniques were commonly practiced in the curriculum of an A-level art class; the specific period where our workshops had been inserted. We became aware that we needed to create different relational conditions to work not with the entire class group but with smaller groups made up of four to six students led by one member of the research team (Trafí-Prats, Duggan and McCauley). Our hope was that by working in small groups, we would build the relation with the students and they would feel less intimidated and more open to engage in ethnographic research, creative methods and experiment with the concepts and activities that we had devised for our workshops.

Location/direction/perspective

In our first workshop we explored the concepts of location/direction/perspective. We wanted to problematise location as more than a spatial coordinate and to conceive it as connected to embodied practices of orientating, inhabiting, and moving through space in daily experiences, such as moving and inhabiting certain rooms or spaces in the school, walking or driving to the school every day, passing through specific thresholds that define the intensive experiences of alignment or alienation with institutional norms and social expectations. We aimed to explore the complicated relation between the lines that make space as a specific projection, surface, and geometry, and how the body relates to them by getting dis/orientated, dis/aligned, un/directed or un/turned by them (Ahmed, 2006). Through conversations, walks and creative activities developed with the students, we began to see their emergent sense of space, the lines and directions that are followed, but also the paths and derivative movements that are created as effect of movement and repetition.

In an initial activity, we asked the students to situate the location of the school, their homes, and other spaces that they habitually visited during the week on copies of the Liverpool’s wards map, an abstract representation that was completely unrelated to students’ embodied and everyday experience. Many did not even recognise that the map represented Liverpool, and felt confused about how and where to locate themselves, their homes, and the school. Such confusion demonstrated that the sense of location is embodied, experiential, and connected to a sense of direction built through habit and inhabitation. Students guessed their potential locations spontaneously turning into Google maps to orientate themselves, while realising that maps are not objective and universal and that the spatial representation provided by Google maps that shows territorial elements like roads, streets, railroads, houses, and locational points did not directly translate into the representation of the wards map, which only contained the lines of administrative borders.

We created an animation inscribing and layering the different points given by the students. Each student’s response is represented with a different colour. None of the points guessed by the students are in the same location in space. The visualisation evokes students’ dis/orientation in the Liverpool wards map, and how a sense of location cannot be disentangled from habit, embodiment, movement and memory.

Figure 1: Visualisation compiling and overlying the various location points provided by students. Each colour corresponds to one student.

In the next activity, students drew maps of their journeys to school. We showed and discussed with them different examples of different visualisations of personal geographies created by artists and writers and asked them to take them as an inspiration to draw a map of their journey that same morning. We also asked them to annotate things like the feeling of leaving home, moving through the streets and approaching school. The maps offered an initial glimpse to students’ itineraries, their sense of location and direction, how they moved through space, and how specific environmental relations emerged as part of such movement.

Figure 2 : Map drawn by student reflecting their journey to school

Figure 3: Map drawn by student reflecting their journey to school

Weeks later, we met the students to elicit further the experiences annotated in the maps. One of the aspects we wanted to learn more was about the experience of crossing thresholds, such as the threshold of moving from being outside in the street or the family’s car to enter the school. In spatial theory thresholds are seen as in-between spaces where realignment between bodies and environmental and constructed elements can occur (Grosz, 2001). Thus, attending to the experience of approaching and moving through these thresholds is important to understand how the school as an environment generates certain alignments, movements, lines of vision, orientations of bodies in space.

Showing students an image of the school’s front door, we asked them two questions, ‘from what direction you arrive to the front door?’ and ‘what is that you do when you arrive to the school entrance?’ We drew lines of the path each followed towards accessing the entrance. Additionally, students described whether they moved quickly, stopped to talk to friends, waited and supervised how a younger sibling entered through a different door, or how they arrived earlier or later to avoid encountering others. After this, we showed students a panoramic of the school’s atrium taken from the point of having passed the entrance threshold and we asked them, ‘what is the first thing that you notice when you enter the school in the morning?’ The answers clearly revealed how orientation and direction are connected to the architectural design of the entrance and the overall school as an open plan revolving around the atrium. From the entrance point, one can see a great portion of the atrium, including tables, offices with transparent walls, one of the kitchens and a corner of the 6th Form hub. One can also see the structure of four floors and the main staircase. Considering this, students reported that as they entered one mentioned the first thing they would do is spot if their friends were sitting in the 6th form hub. Others reported looking upwards to ascertain any light on the third floor to decide if they could go and sit there. One mentioned that he would walk and attend to potential voices and clattering plates in the cafe at the back; hearing such sounds which indicated that the morning free milk and toast would be already available.

Figure 4: Marking the directions students enter the school

Figure 5: Discussing the first thing students do when they enter the school

Capture/envelopment/atmosphere

In another workshop, we explored how atmospheres shaped the experience of the school building. In architecture, atmosphere designates the seemingly immaterial dimension of sensation and affect and contributes to the sensational and relational quality of a building or environment. Through the arrangement of specific design choices of material, light, sound, texture, scents, a space can feel expansive or tight, intimate or distant, exposed or concealed, vibrant or eerie (Pallasmaa, 2012; Spence, 2020). The affective qualities of atmospheres are not necessarily given in advance but have to be expressed through space-temporal events, in which diverse and multiple forces conjoin or enmesh, to disclose what ‘appears’ as elemental, but is better conceived as generative, in the space-time atmosphere (Ash, 2021; MacCormack, 2019). Therefore, to foster atmospheric sensing, we developed activities that promoted immersion in space-time events along with the cultivation of skilful embodiment and techniques of capture that could amplify and intensify sensory practice (Engelman & MacCormack, 2018).

We began by discussing with students their perception of rooms in the school building where they develop their daily and weekly activity by looking at the school floor plans provided by the architects. The plans are an abstract and technical representation of the building, as such they were useful to notice and discuss the differences between space as projection and space as lived and felt through the effects of its form, materiality, texture, light, sound. This helped to initiate a conversation of how the environmental conditions of different spaces, the noise, food smell, busyness, lack of light shaped the quality of the experiences developed in these spaces.

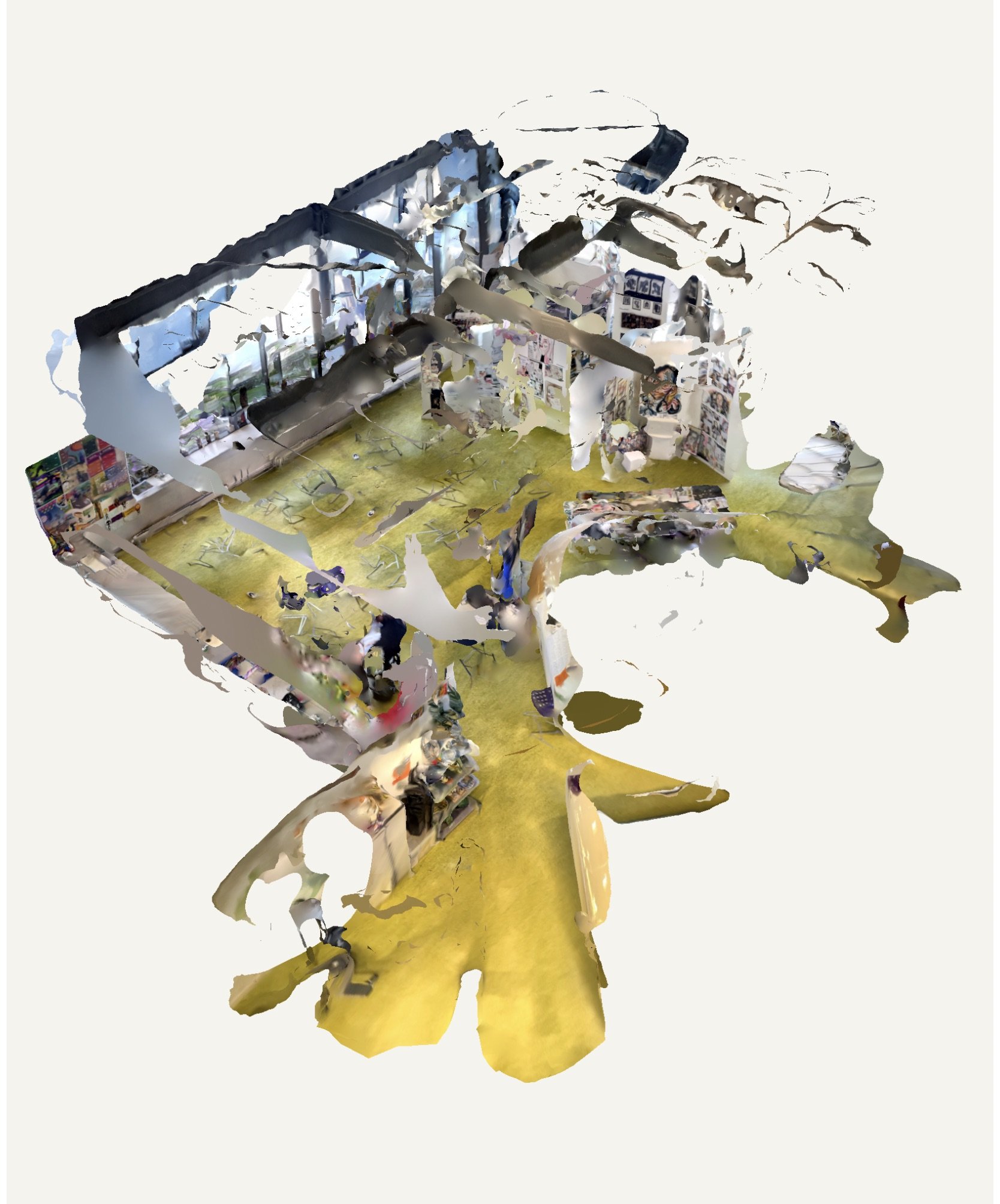

In a second activity, we showed students how to scan few rooms where they reported to spend more time. For this we employed Polycam, an app that uses the Lidar camera in the iPads to create a fairly realistic but at sections blurry, stripped and unfinished images that evoke the tone of embodied movement and specific environmental conditions in surfaces. The points in the room where the body moves quickly or directs the attention more incisively are rendered with less or more detail. Similarly, surfaces that are excessively smooth, shiny or white are simply not recorded. This could, for example, wipe out from the scanning of a classroom entire rows of tabletops, only recording part of their legs. The resulting imperfect images of the room scans generated by the students became useful to provoke discussion around how and why some aspects of the room had been rendered with high quality whereas others appeared blurry or blank, bringing awareness to material and atmospheric qualities of the spaces. Also, by noticing the movement performed in the process of scanning a room, which commonly involves moving the arms holding the iPad up, down, around while meandering the room in wiggly lines, the students noticed additional aspects of the space that they take for granted, the shape of the room, the effects of the light in surfaces, the volumes that are in space and that make them move in specific ways, the depth and height of spaces, etc.

Figure 6: Lidar scan of the art space on the third floor

Figure 7: Lidar scan of the theatre's stairs

As one student scanned a specific room another student in the group observed and mapped the direction of the movement with a line drawn in the Procreate app over an image of the same room. These mappings were useful to discuss with students how they moved through the spaces, what elements in the room they pay attention to, what parts of the room they did not go, etc. Students were quite curious when different scans of the same room generated looked different. The emergent discussion pointed at potential differences in speed, gesture, movement, light when scanning the space, which reinforced our own understanding of scanners not as objective measuring tools, but as prothesis and extensions of the sensing-moving body.

Figure 8: Line drawing representing another student’s movement through the art space in the process of scanning it.

Figure 9: Line drawing representing another student’s movement through the theatre's stairs in the process of scanning them.

In a later activity we utilised screen captures of the room scans and exported them into the app Procreate. Using the app’s layers, colour and brushes tools, students were invited to map sound, air and scent felt in the selected rooms. This happened in real time while being in the rooms. Each mapping (sound, air, scent) was situated on differentiated layers over the image of the room. The composite image deploys a speculative representation of the room’s atmospheres, foregrounding the multi-sensory aspect of architecture, and how it shapes the ways spaces are lived, perceived, and described (Spence, 2020).

Figure 10: Students’ mapping of air and scent in the music area.

Figure 11: Students’ mapping of sound in the music area.

Movement/Transition/Flow

Architectural space unfolds and actualizes when one moves, helping us understand architecture as a participatory event that shapes the raw possibilities of movement and corporality in specific ways (Ellsworth, 2004). In a further series of activities, we explored how students moved through the school spaces. We used video to defamiliarize the perception of habitually transited spaces, and to direct students' attention to the constructed qualities of the building’s geometry, and the embodied relation with its materiality (Bruno, 2014; Pallasmaa, 2012). The activities also inquired on how students moved from one space to another in the school, what were their habitual and chosen paths, which spacetimes generated ebbs and flows in the transition between spaces and how these shaped sensations of a space being obtrusive, vertiginous, smooth, overwhelming, encompassing, dull, etc.

In an initial activity, we used the school floor plans and invited the students to trace their weekly and daily itineraries through the building; from the time they arrived, to the time they exited. This was useful to identify the different rooms they used, what did they do in these rooms and how did they move from one room to another. It was informative too to see how transitions through the building commonly involved the use of the 6th form stairs, and the navigation through a busy atrium. We also learned that students attended different subjects at different periods but that the art space, the 6th form quiet study room, and the 6th form hub tended to be spaces where Year 12 students reencountered others during period breaks, recess, and lunchtime.

Following this, we showed the students a video- animation created by BDP architects during the design stage of the school building that simulated the entrance into the building through a smooth and pleasant movement from the front facade, the main school gate, and into the large atrium. It foregrounded the bold architectural volume of the school theatre, both from the perspective of the façade and the atrium whilst evoking a lightly and welcoming atmosphere through projected lights and shadows consistently moving with the camera tracking. Students compared the animation with their own experiences trying to enter the building, pointing at how passing both doors was the opposite of smooth and required to be buzzed in by staff at the reception desk. Often, they found themselves waiting to be let in and stuck between the two sets of doors. The proposition of thinking the actual experience of the entrance space with film aimed to highlight the potential of film as a medium to create an imagined sense of spatial flow, and to recognize other potentials for movement and sensation different to the manifested ones in the current spatial arrangements (Ellsworth, 2004). As Pallasmaa (in Pallasma and Zambelli, 2020) writes, “The lived space of cinema offers a great lesson for us architects, who tend to see our craft through a formal bias. Great film directors show us that architecture can evoke and maintain experiences of alienation or terror, melancholy or fear, amusement or bliss” (p. 57).

Figure 12: Still from a video-animation simulating the entrance to the building. Credit: BDP architects.

Figure 13: Still from a video-animation simulating the entrance to the building. Credit: BDP architects.

Figure 14: Still from a video-animation simulating the entrance to the building. Credit: BDP architects.

Following the viewing and discussion of the video-animation, we asked students to design a potential itinerary through the school and video-record it. We trained them to walk behind the camera so to capture the tracking through space rather than their actual bodies moving. We used an extra wide-lens camera which deformed the geometry of the space, prompting students to think and imagine other possible forms, surfaces and topologies. Additionally, the process of video-recording and later editing with iMovie, allowed the students to experience the school-space as open-ended and a variating composition of flows, drifts, speeds, emanations, successions rather than a fixed container (Grosz, 2001)

Figure 15: Mapping on the school buildings floor map the itinerary that we video-recorded with a group of students.

Figure 16: Still from the navigational video created by the students as we walked the devised itinerary. The deformed lines created by the wide-less camera are quite noticeable.

Figure 17: Still from the navigational video created by the students as we walked the devised itinerary. The video is effective in conveying the sensational transformations of passing from one space to another, capturing transformations in light, texture, sound, noise, pace.

In later interactions with the students, we have noticed that these initial set of workshops had been generative in extending students sensorial awareness of the school building. The different activities and experiments that we conducted with them were productive in eliciting sensational processes concerning vision, scent, form, sound, temperature, light, texture, time that shaped their perception of space and defined the ways in which they described their experiences of moving and dwelling in the school building, including the effects that these have on being, learning and socialising. The workshops deployed a space for thinking and talking about the lived experience of being in the building and studying in the building, and to do it considering vision with other senses and sensations.

We noticed a richer environmental awareness manifesting during Ling Tan’s workshop (March 9-11, 2022), when students collected data independently of self-selected parts of the building with their own mobile phones using Ling Tan’s app SUPERPOWER. The aim was for the students to use the collected data to propose and design conceptual prototypes in cardboard and other basic materials. Students’ justification of their prototypes and why certain spaces in the school needed improvements manifested a grasp of the multisensorial aspects of spatial experience and how architecture can modulate felt experiences like noise, flow, heat, crowdedness, textural hardness to improve the lived experiences of these spaces. A more specific overview of Ling Tan’s workshops can be read in the next blog instalment.

References

Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer phenomenology: Orientations, objects, others. Duke University Press.

Ash, J. (2013). Rethinking affective atmospheres: Technology, perturbation and space-times of the non-human, Geoforum, DOI:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.05.006.

Bruno, G. (2014). Surface: Matters of aesthetics, materiality, and media. University of Chicago Press,

Engelmann, S. & McCormack, D. (2018). Sensing atmospheres. In C. Lury, R. Fensham, A.Heller-Nicholas, S. Lammes, A. Last, M. Michael & E. Uprichard (Eds.), Routledge handbook of interdisciplinary research methods. Routledge.

Ellsworth, E. (2004). Places of learning: Media, architecture, pedagogy. Routledge.

Grosz, E. (2001). Architecture from the outside: Essays on virtual and real space. MIT Press.

MacCormack, D. (2019) Atmospheric Things: On the Allure of Elemental Envelopment. Duke University Press.

Pallasmaa, J. (2012). The Eyes of the skin: Architecture and the senses (3rd ed.) Wiley.

Pallasmaa, J. & Zambelli, M. (2020) Inseminations: Seeds for architectural thought. Wiley.

Pink, S. (2015). Doing sensory ethnography, 2nd Edition. Sage Publications.

Pink, S., Houst, H., Postill, J. Hjorth, L. Lewis, T. & Tacchi, J. (2015). Digital ethnography: Principles and practice. Sage publications.

Spence, C. (2020). Senses of place: architectural design for the multisensory mind. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, DOI:10.1186/s41235-020-00243-4